Hoe kan een paddenstoel een bos redden? Nou, bijvoorbeeld door haar sporen te laten vliegen en zichzelf te vermenigvuldigen, zodat de bosgrond verriijkt wordt met haar ‘wortels’, het mycelium. Of door zich te laten plukken en zich te laten verkopen, en het geld terug naar de bosbeheerders te laten sturen, zodat die geen bomen hoeven te kappen voor een snel inkomen uit zaken als houtskool.

vruchten van het wood wide web

Paddenstoelen zijn vergelijkbaar met vruchten als appels of kersen, alleen groeien ze niet aan een boom, maar aan een ondergronds netwerk van schimmeldraden. Die draden brengen niet alleen de paddenstoelen voort, maar maken de grond ook vruchtbaar voor een heleboel andere organismes. Al die schimmeldraden die de boomwortels helpen groeien, heten samen het ‘mycorrhiza’.

De BBC maakte een mooi filmpje van het ‘Wood Wide Web‘ waarmee deze schimmels communiceren met plantenwortels in de bosgrond. Behalve mineralen, suikers en water, wisselen ze bijvoorbeeld ook signaalstoffen uit om aan te kondigen dat er rovers, brand, droogte of ziektes op komst zijn. Andere organismes kunnen zich daar dan tegen wapenen, bijvoorbeeld door hun bladeren te laten vallen of vieze luchtjes af te scheiden.

heksenkringen

Paddenstoelen groeien vaak aan de uiteinden van hun schimmelnetwerken, om daarvandaan het volgende stuk grond of hout over te kunnen nemen. Daardoor tref je ze in ronde kringen: ‘heksenkringen’. Hoewel we inmiddels weten dat er voor het vormen van die cirkels geen kwaadwillige magiërs benodigd zijn, is het voor de meeste mensen toch goed een beetje bang van die kringen te zijn – paddenstoelen kunnen immers giftig zijn, en maar weinig mensen hebben de kennis om het verschil tussen een dodelijk exemplaar en geneeskrachtig exemplaar te kunnen zien. Net als bij planten (en mensen?), zijn er families waarin de onschuldigenen en de schuldigen nauwelijks van elkaar te onderscheiden zijn, maar ook families waarin dat verschil makkelijk vast te stellen is.

Lekkere Russula’s

Twee van de eetbare paddenstoelen die je bij Mobile Orchards kan kopen, komen uit de familie van de Russula’s. Dat is een van de families waarin je het onderscheid tussen gezond en giftig best makkelijk kan testen: de oneetbare smaken heel scherp. Dat merk je al als je ze even tegen je tong houdt. Ze zijn niet giftig genoeg om je daarvan veel last te geven (tenzij je allergisch bent).

Gelukkig weten onze Zambiaanse paddenstoelenverzamelaars ook zonder proeven heel goed welke te eten zijn en welke niet. Zij drogen de russula’s, waarna ze nog jaren houdbaar zijn. Omdat de paddenstoelen in het regenseizoen geplukt worden, kan het gebeuren dat ze een beetje naar rook smaken: iemand heeft ze dan naast het houtvuur gelegd om ze te drogen, vaak omdat het ging regenen.

De Russula’s die wij in Zambia kopen heten daar ‘Munya’ en ‘Busefwe’, maar Europese paddenstoelendeskundigen als Bart Buyck kennen ze als de ‘Russula Cellulata var. Ntama’ en de ‘Russula Ciliata’. De kleverige Russula Ciliata komt in verschillende kleuren voor, de Cellulata zijn vaak een beetje oranje-bruin met een witte onderkant. Net als de Nederlandse Russula’s vormen ze allianties met bomen: in Europa werken Russula’s bijvoorbeeld samen met berken of eiken, in het Zambiaanse miombobos met bomen als de Afzelia africana, de Afrikaanse Mahonie, die veel te vaak geoogst wordt, vanwege haar mooie hout. Lokale bosbewoners krijgen meestal maar een paar euro voor een hele boom – een prijs die we al kunnen verslaan met een paar blikjes russula! Dan kan de boom gewoon blijven staan, zodat ze volgend jaar weer kunnen oogsten.

Foto: Roeli Andrea 2024

Of dat ook echt zal lukken, moeten we de komende jaren uitzoeken. Inkomsten uit de verkoop van paddestoelen gaan meestal naar de vrouwen, terwijl inkomsten uit hout meestal naar de mannen gaan. Om te voorkomen dat die achterblijven, verkopen we bijvoorbeeld ook meubels en sierraden van takkenhout, waarvoor de stam kan blijven staan. We houden het effect van ons werk in de gaten met behulp van satellietbeelden, de burgerwetenschappelijke methodes van voedsel-uit-het-bos en studenten die ons werk ter plekke onderzoeken.

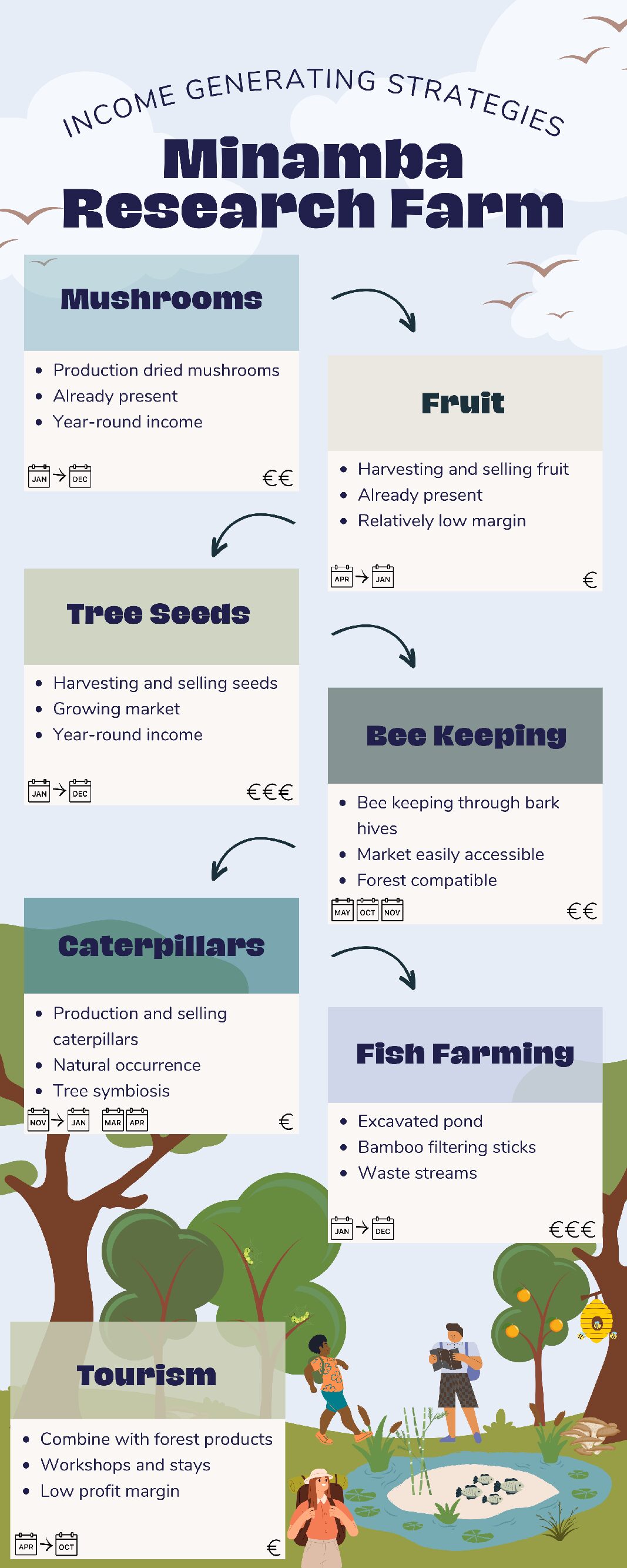

handleiding eetbaar bosbeheer

Om lokale mensen enig inzicht te geven in de opbrengst die duurzaam bosbeheer hen kan bieden, werken we daarnaast ook aan een handleiding die je kan gebruiken om je bos en oogst te monitoren. Daarmee kan ook een grove inschatting van de toekomstige waardes worden geven – qua geld, maar bijvoorbeeld ook qua bouwmaterialen of voeding. Omdat bosproducten als de paddenstoelen doorgaans veel gezonder zijn dan voedsel dat je met geld koopt, vragen wij de verkoopsters een ruime voorraad voor hun gezin apart te leggen voordat ze het restant verkopen. Bij winstvoorspellingen kijken we dus niet alleen maar naar het geld – het bos moet ook vooral gezond en lekker zijn!

Foto: Jara van den Berg 2024

recept paddenstoelenpaté

Dat de Zambiaanse Russula’s ook echt bizar lekker kunnen zijn, bewees de Zoetermeerse kok Dirk met zijn recept voor een tartelette met paddenstoelenpaté, losjes gebaseerd op dat van chickslovefood. Toen we zijn paddenstoelenpaté van onze Russula Cellulata op de markt lieten proeven, was iedereen gelijk om. Het lijkt het ideale hapje voor een feestelijk diner, en nog vegetarisch ook! Voor de gelegenheid maakte Dirk zelfs een glutenvrije variant.

Dirk gebruikte:

1 ui

1 teentje knoflook

300 gram verse paddenstoelen (bijv. kastanjechampignons)

1 takje verse tijm

125 gram roomkaas

1 handje krulpeterselie

4 tartelettes of ronde toastjes

10 gram gedroogde paddenstoelen

50 gram bevroren kersen

1 eetl. honing

Voorbereiden

1 Maal (koffiemolentje/kleine keukenmachine) de gedroogde paddenstoelen tot een fijn poeder, of gebruik een blikje voorgemalen gerookte Russula’s

2 Snijd de ui, knoflook en paddenstoelen grof.

3 Doe de ui, knoflook en paddenstoelen in een keukenmachine en maal dit tot hele kleine stukjes. Verhit dan een scheutje olie in een koekenpan en bak het paddenstoelenmengsel tot dit helemaal gaar is.

4 Breng het mengsel op smaak met de poeder van de gedroogde paddenstoelen.

5 Haal de pan van het vuur, laat een beetje van het vocht weglopen en meng de paddenstoelen met de tijm, roomkaas en wat fijngehakte peterselie. Breng op smaak met peper en zout.

6 Schep de paddenstoelenpaté in een spuitzak en bewaar koud.

Serveren

1 Verwarm de kersen met de honing in een steelpannetje en plet ze met een houten lepel zodat het sap eruit loopt.

2 Leg een kers in elke tartelette of op elk toastje.

3 Knip een puntje van de spuitzak met paddenstoelenpaté en vul de tartelette of toastje met de

paddenstoelenpaté.

Glutenvrije variant

I.p.v. de tartelette of het toastje kan je bijvoorbeeld een schijfje koolrabi gebruiken. Schaaf plakken van 4 mm van de koolrabi en steek er rondjes van 3 cm uit. Blancheer deze 3 tot 4 minuten in kokend water en laat ze afkoelen in ijskoud water.

Om koks als Dirk te helpen, bieden we de Zambiaanse Russula’s binnenkort ook gerookt en gemalen aan in een klein blikje dat door de brievenbus past. Dan heb je gelijk een mix van gedroogde Russula Ciliata en de Russula Cellulata, voor een prijs die kan concureren met de gedroogde russula’s die je in de delicatessenwinkel koopt. Laat ons vooral weten wat je ermee doet, we zijn heel benieuwd naar het resultaat!

Foto: Desh Chisukulu 2024